# Basic Theory of Binary Trees

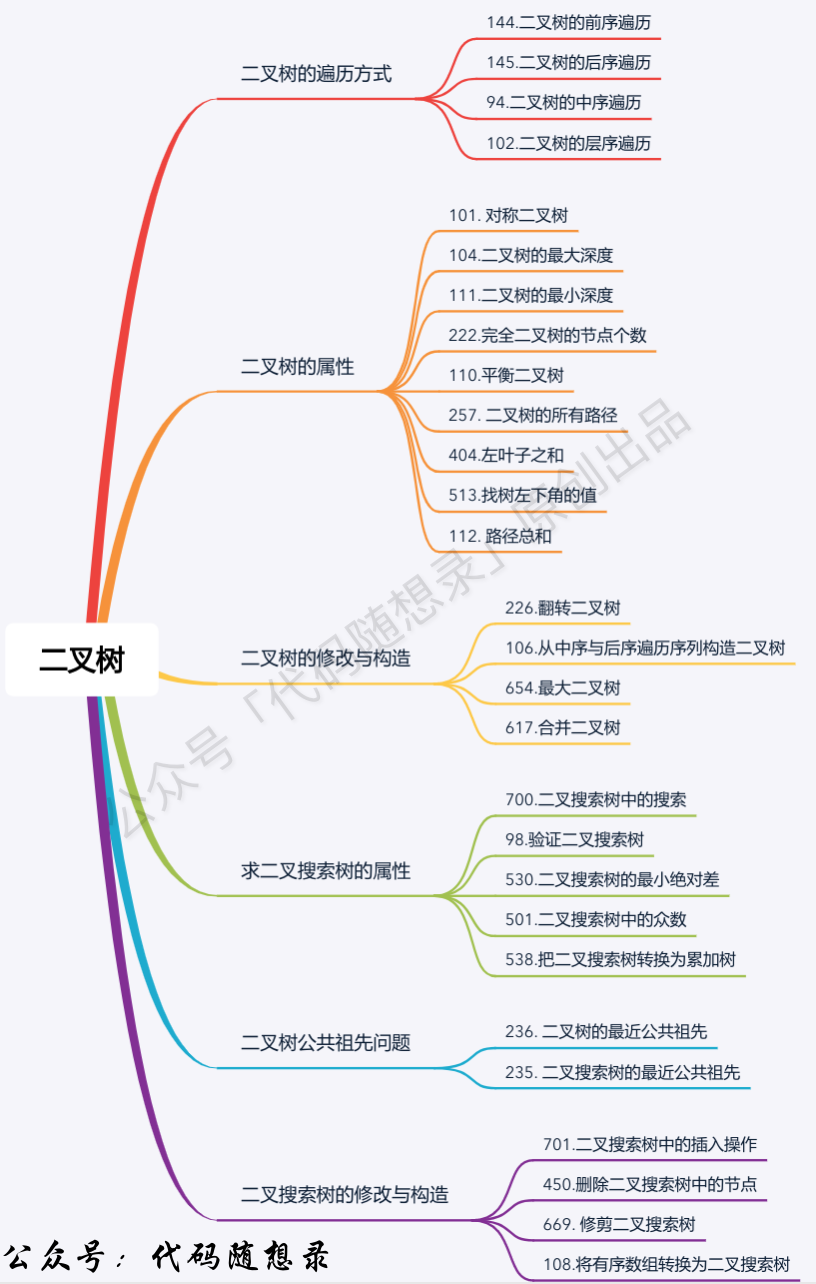

# Problem Categories

The outline of problem categories is as follows:

When it comes to binary trees, everyone is actually quite familiar with them. In this article, I don't want to retread textbook-style the basic content of binary trees, so I will focus on some of the key points.

I believe that as long as you patiently read through, you will gain something valuable.

# Types of Binary Trees

During our problem-solving process, binary trees have two main forms: full binary trees and complete binary trees.

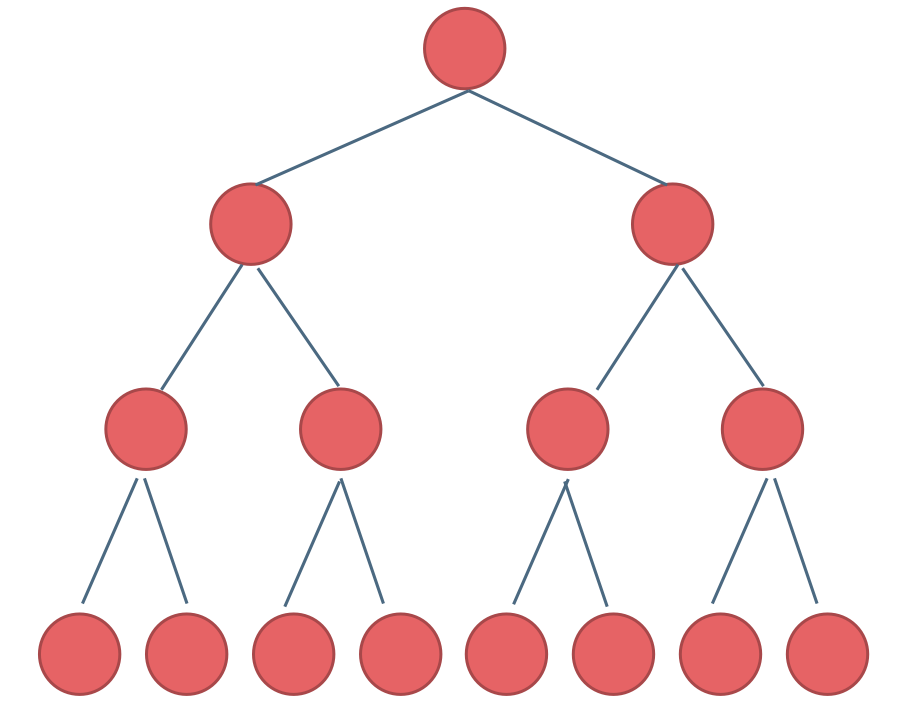

# Full Binary Tree

A full binary tree is one in which every node has either zero or two children, and all leaves are at the same level.

As shown in the diagram:

This binary tree is a full binary tree and can be described as a tree of depth k with 2^k - 1 nodes.

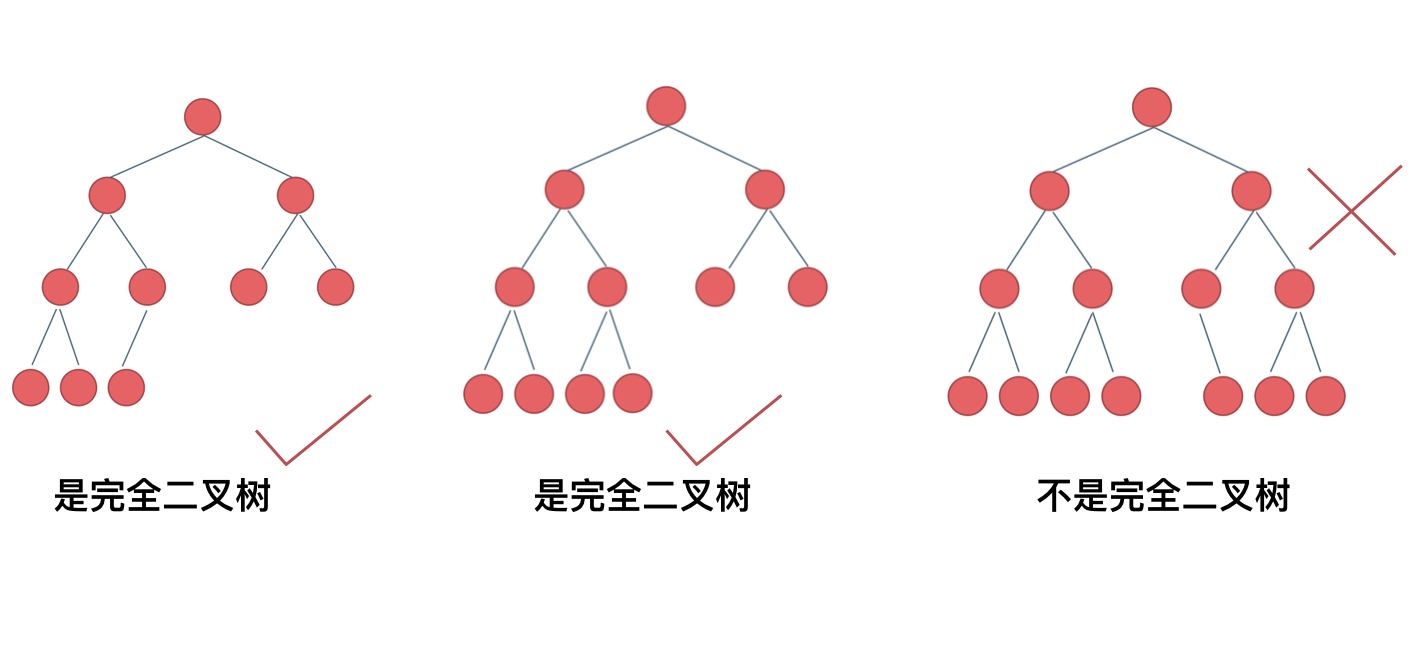

# Complete Binary Tree

What is a complete binary tree?

The definition of a complete binary tree is as follows: A complete binary tree is a binary tree where each level, except possibly the last, is completely filled, and all nodes are as far left as possible. If the bottom level is the hth level (starting from 1), then this level contains 1 to 2^(h-1) nodes.

It's crucial to understand the definition of a complete binary tree, as many people might not fully grasp it.

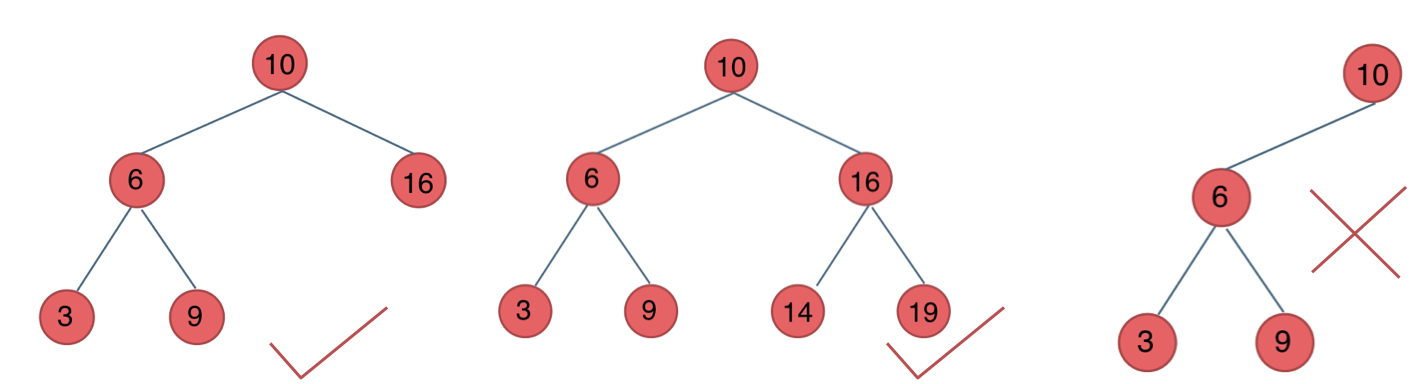

Here's a classic example:

Believe it or not, many people get confused about whether the last binary tree is a complete binary tree.

Earlier, we mentioned that a priority queue is essentially a heap, and a heap is a complete binary tree that maintains order between parent and child nodes.

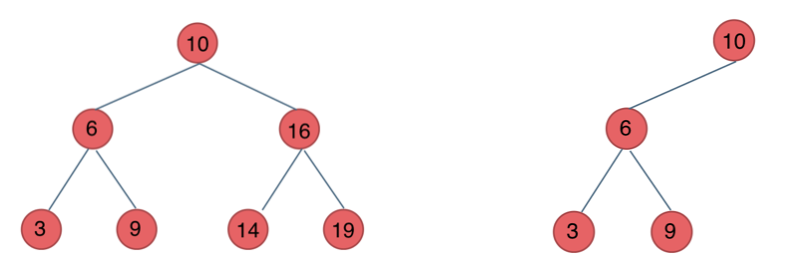

# Binary Search Tree

The previously introduced trees are devoid of values, but a binary search tree has values and is an ordered tree.

- If its left subtree is not empty, all the nodes on the left subtree have values less than its root node.

- If its right subtree is not empty, all the nodes on the right subtree have values greater than its root node.

- Both left and right subtrees are also binary search trees.

Both of the following trees are search trees:

# Balanced Binary Search Tree

A balanced binary search tree, also known as an AVL (Adelson-Velsky and Landis) tree, has the property that the absolute height difference between the left and right subtrees does not exceed 1, and both subtrees are also balanced binary search trees.

As depicted below:

The last one is not a balanced binary tree because the absolute height difference between its left and right subtrees exceeds 1.

In C++, the underlying implementation of map, set, multimap, and multiset is a balanced binary search tree. Consequently, the time complexity of insertion and deletion operations for map and set is logn. Note that this does not apply to unordered_map and unordered_set; these are implemented using hash tables.

When coding algorithms in your familiar programming language, you should know how commonly used containers are implemented. Understanding the performance of your code is crucial!

# Storage Methods for Binary Trees

Binary trees can be stored using linked or sequential storage.

Link-based storage employs pointers, while sequential storage uses arrays.

As the names imply, sequential storage elements are contiguous in memory, whereas linked storage uses pointers to link nodes scattered across different addresses.

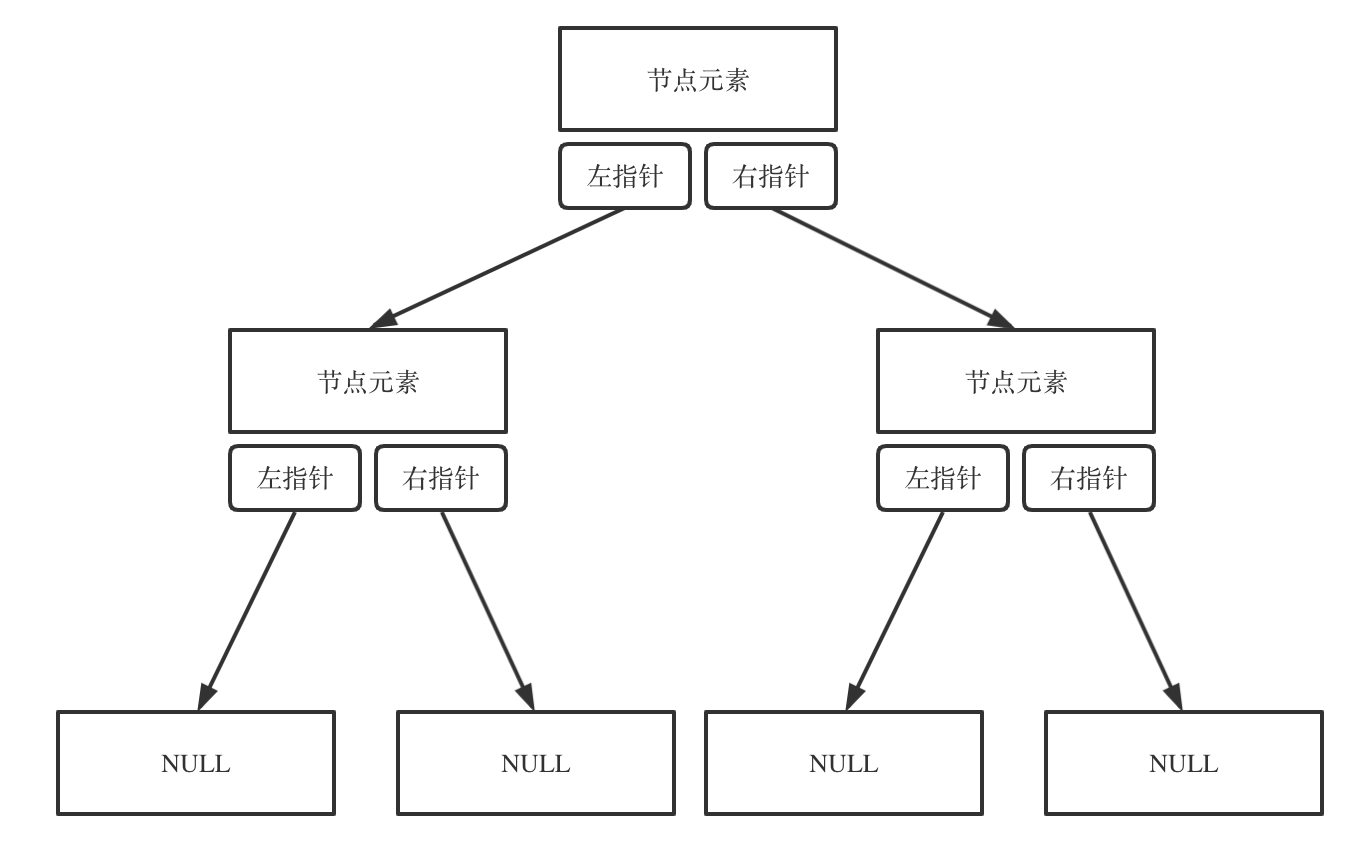

Linked storage is depicted as follows:

Linked storage is something everyone is quite familiar with, so let's explore how sequential storage is done.

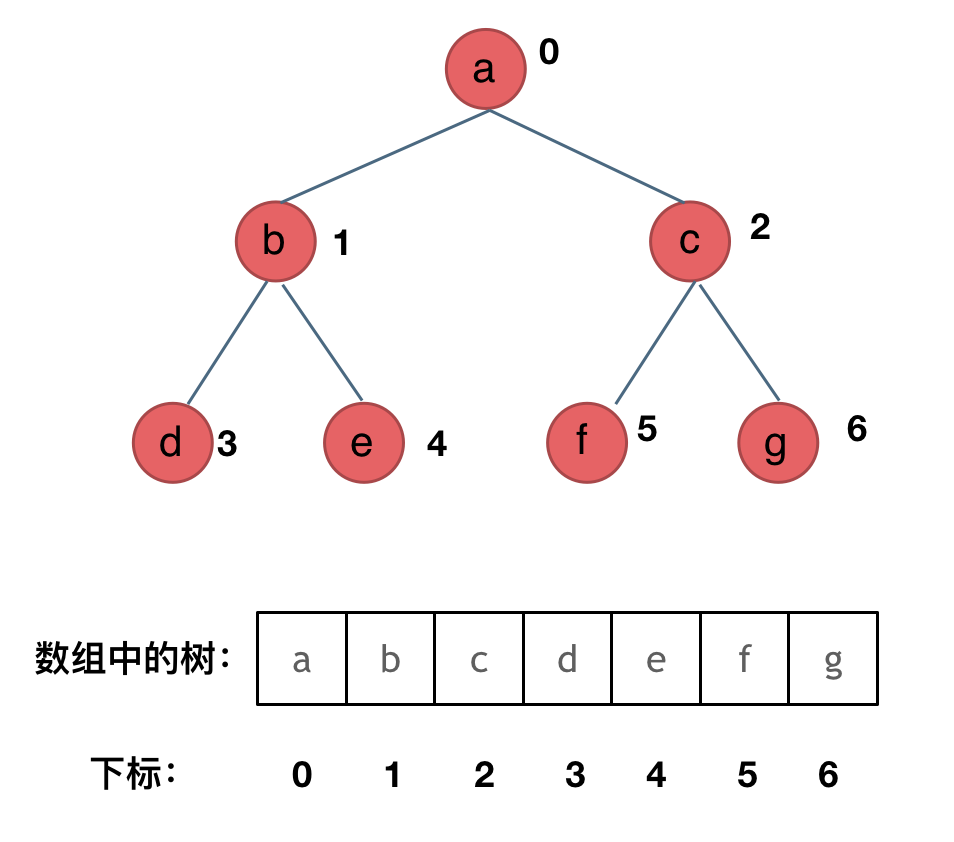

It essentially involves using an array to store a binary tree, as shown in the diagram:

How do you traverse a binary tree stored in an array?

If the parent node's array index is i, then its left child is at i * 2 + 1, and its right child is at i * 2 + 2.

However, a linked representation of binary trees is more intuitive to understand, so we usually represent binary trees using linked storage.

Thus, it's important to understand that arrays can also represent binary trees.

# Traversal Methods of a Binary Tree

Regarding the traversal methods of binary trees, one should know the basic methods of binary tree traversal.

Some of you may know pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversals and might even be aware of level-order traversal but lack a framework.

I'll list the different traversal methods, and you can string them together systematically.

Binary trees primarily have two traversal techniques:

- Depth-first traversal: First, go deeper; upon reaching leaf nodes, backtrack.

- Breadth-first traversal: Traverse layer by layer.

These are the most fundamental traversal methods in graph theory, which I'll cover when discussing graphs later.

Leading to the following traversal techniques from depth-first and breadth-first traversals:

- Depth-first traversal

- Pre-order traversal (recursive, iterative)

- In-order traversal (recursive, iterative)

- Post-order traversal (recursive, iterative)

- Breadth-first traversal

- Level-order traversal (iterative)

In depth-first traversal, there are three orders: pre-order, in-order, and post-order. Some of you might get confused about these orders. Let me teach you a trick:

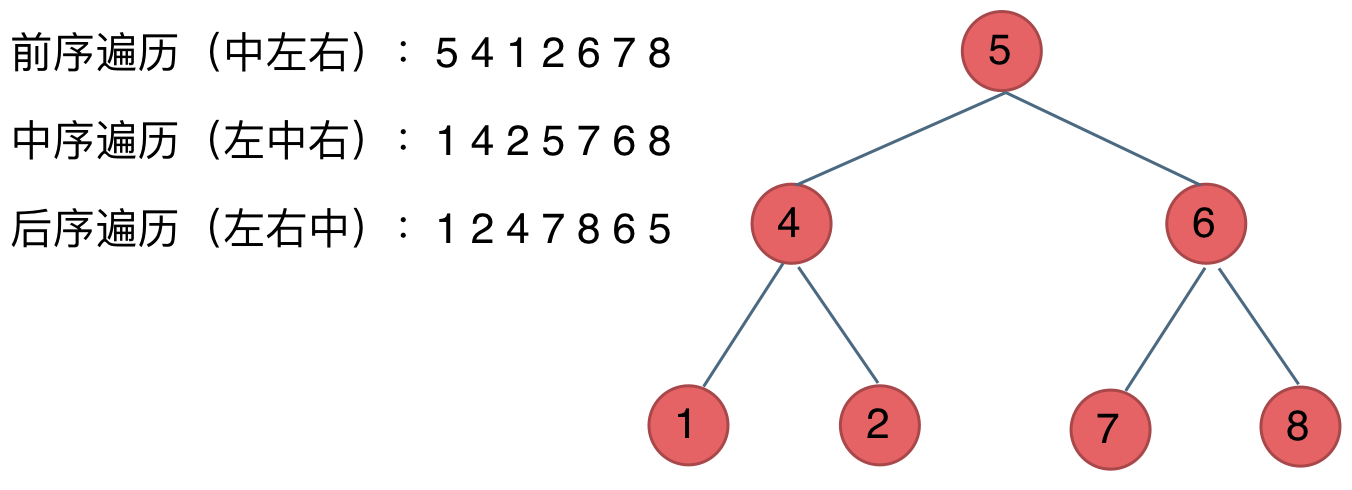

Here, pre-order, in-order, and post-order refer to the middle node's traversal order. Just remember that these terms refer to the order of visiting the middle node.

Take a look at this diagram to check if your understanding of pre-order, in-order, and post-order is accurate.

- Pre-order traversal: middle-left-right

- In-order traversal: left-middle-right

- Post-order traversal: left-right-middle

Refer to the diagram below to ensure your understanding of pre-order, in-order, and post-order is accurate.

Finally, I want to discuss the implementation of depth-first and breadth-first traversal in binary trees. When solving binary tree problems, we often use recursion for depth-first traversal, implementing pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversals. Recursion is quite convenient in such cases.

As mentioned earlier, stacks are essentially a way to implement recursion, which means that the logic for pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversals can be achieved using stacks through recursion.

On the other hand, breadth-first traversal is typically implemented using queues. The characteristics of a queue, like first-in, first-out, make it suitable for traversing binary trees layer by layer.

This gives us another perspective on applying stacks and queues.

We'll cover specific implementations later, but for now, it's important to understand these theoretical foundations.

# Definition of a Binary Tree

As mentioned earlier, binary trees have two storage methods: sequential storage using arrays and linked storage. Sequential storage doesn't have much to discuss, so let's look at how binary tree nodes are defined for linked storage.

C++ code is as follows:

struct TreeNode {

int val;

TreeNode *left;

TreeNode *right;

TreeNode(int x) : val(x), left(NULL), right(NULL) {}

};

2

3

4

5

6

You'll notice that the definition of a binary tree node is quite similar to that of a linked list. Compared to a linked list, a binary tree node has an additional pointer. It has two pointers, each pointing to a left or right child.

Here, I want to remind you to pay attention to how binary tree nodes are defined.

During on-site interviews, the interviewer might ask you to write code by hand, so you should practice writing definitions of data structures and simple logic on paper.

Since when doing problems on LeetCode, the node definitions are already provided, sometimes when you're expected to define a node during an interview, you might find yourself at a loss!

# Summary

The binary tree is a fundamental data structure, a common guest in algorithm interviews, and the foundation of numerous other data structures.

In this article, we've introduced the types of binary trees, storage methods, traversal techniques, and definitions, providing a comprehensive overview of key points to help you solidify your understanding.

Speaking of binary trees, recursion inevitably comes into play. Many find recursion both familiar and enigmatic. Recursion-based code is often brief, but it can be a case of "easy to read, hard to write."

# Code in Other Languages

# Java:

public class TreeNode {

int val;

TreeNode left;

TreeNode right;

TreeNode() {}

TreeNode(int val) { this.val = val; }

TreeNode(int val, TreeNode left, TreeNode right) {

this.val = val;

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# Python:

class TreeNode:

def __init__(self, val, left = None, right = None):

self.val = val

self.left = left

self.right = right

2

3

4

5

# Go:

type TreeNode struct {

Val int

Left *TreeNode

Right *TreeNode

}

2

3

4

5

# JavaScript:

function TreeNode(val, left, right) {

this.val = (val===undefined ? 0 : val)

this.left = (left===undefined ? null : left)

this.right = (right===undefined ? null : right)

}

2

3

4

5

# TypeScript:

class TreeNode {

public val: number;

public left: TreeNode | null;

public right: TreeNode | null;

constructor(val?: number, left?: TreeNode, right?: TreeNode) {

this.val = val === undefined ? 0 : val;

this.left = left === undefined ? null : left;

this.right = right === undefined ? null : right;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

# Swift:

class TreeNode<T> {

var value: T

var left: TreeNode?

var right: TreeNode?

init(_ value: T,

left: TreeNode? = nil,

right: TreeNode? = nil) {

self.value = value

self.left = left

self.right = right

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# Scala:

class TreeNode(_value: Int = 0, _left: TreeNode = null, _right: TreeNode = null) {

var value: Int = _value

var left: TreeNode = _left

var right: TreeNode = _right

}

2

3

4

5

# Rust:

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct TreeNode<T> {

pub val: T,

pub left: Option<Rc<RefCell<TreeNode<T>>>>,

pub right: Option<Rc<RefCell<TreeNode<T>>>>,

}

impl<T> TreeNode<T> {

#[inline]

pub fn new(val: T) -> Self {

TreeNode {

val,

left: None,

right: None,

}

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public class TreeNode

{

public int val;

public TreeNode left;

public TreeNode right;

public TreeNode(int x) { val = x; }

}

2

3

4

5

6

7