# Summary of Greedy Algorithm

When I started explaining the greedy series, I mentioned that the order of the explanations would not strictly go from simple to difficult.

This is because simple greedy problems might be overly simple, to the extent that they don't even feel like greedy problems. If I were to discuss simple greedy problems for several days in a row, I suppose everyone would get impatient and feel that there is nothing significant to learn about greedy problems.

However, difficult problems in greedy algorithms can indeed be quite challenging, so I introduced them by alternating between simple and difficult to keep the difficulty level moderate. Moreover, greedy algorithms do not follow any specific framework or pattern, so the order of practice doesn't have to be strict.

Overall, the difficulty of the problems I introduced in the greedy series increased in a step-wise pattern, and observant followers might have noticed that.

In the previously covered backtracking series, you may recall that I explained the problems strictly in a gradual sequence from framework to difficulty, which differs from greedy algorithms because missing the order in backtracking can lead to poor practice outcomes.

Similarly, the backtracking series did not allow an alternation of simple and difficult problems because there is a cause-and-effect relationship between them, and those who followed the series would appreciate the attention to detail.

Every series has its unique characteristics, and I adjust the teaching approach accordingly. The daily problem recommendations are not random; they result from careful overall planning and further contemplation of specific problems.

In this summary of the greedy series, I will roughly categorize the problems according to difficulty and type.

The comprehensive summary of greedy algorithms officially begins:

# Basics of Greedy Theory

In the Greedy Algorithm Fundamentals (opens new window) introduction, we addressed common questions about greedy algorithms.

- Is Greedy straightforward, like common sense?

Those who have practiced the problems will find that greedy approaches can often be clever and not as straightforward as initially perceived.

- Are there any fixed patterns in greedy algorithms?

Greedy algorithms have no fixed patterns or frameworks. You need to practice and develop a sense for identifying greedy approaches.

- What exactly qualifies a problem as a greedy problem?

In my opinion, if deriving a local optimum can lead to a global optimum, it is a greedy problem. If a local optimum isn't found, it's probably just a simulation problem. (This is not an authoritative explanation, just my personal take.)

You don't need to worry too much about categorizing problems as greedy or not; it's too academic. As long as you can solve the problem, that's all that matters.

- How do you know if a local optimum can lead to a global optimum? Is there a mathematical proof?

When solving greedy problems, further data proofs are generally unnecessary. You can manually simulate the solution, and if no counterexample is found, you should try greedily. During an interview, if your code passes test cases, or if you can logically justify your approach, that's sufficient.

Much like using 1 + 1 = 2, you don't need to prove why 1 + 1 equals 2. (This example might be extreme, but the principle holds.)

I believe that after reading Greedy Algorithm Fundamentals (opens new window), you should have a basic understanding of greedy algorithms.

# Simple Greedy Problems

The following three problems are simple ones, where you may find that greedy algorithms feel just like common sense. Yes, the problems below rely on common sense, yet I specifically analyzed what constitutes the local and global optimum. Greedy method must justify its choice:

- 0455.Assign Cookies (opens new window)

- 1005.Maximize Sum Of Array After K Negations (opens new window)

- 0860.Lemonade Change (opens new window)

# Intermediate Greedy Problems

In intermediate problems, relying solely on common sense might not be enough, and the ingenuity of greedy algorithms becomes evident.

# Solving Stock-Problems with Greedy Algorithms

While stock problems are predominantly dynamic programming domain, greedy approaches can solve them as well. These two problems illustrate this capability, though they are not the only examples.

- 0122.Best Time to Buy and Sell Stock II (opens new window)

- 0714.Best Time to Buy and Sell Stock with Transaction Fee (opens new window) It is suggested to understand this one through dynamic programming for a less convoluted solution.

# Balancing Two Dimensions

When two dimensions influence each other, considering both simultaneously often results in oversights. Prioritize determining one dimension before the other.

In the explanation of this problem, I emphasized the importance of understanding the programming language used. During the simulation of line-cutting, using list (linked list) in C++ over vector (dynamic array) significantly increases efficiency.

Hence, a detailed explanation was provided in Queue Reconstruction by Height (Vector Principle Explanation) (opens new window) to illustrate why list is faster than vector from a principle standpoint.

You need to understand your programming language's internal mechanisms to write efficient algorithms!

# Difficult Greedy Problems

Some problems here can be very challenging to think of, even if you've encountered them before. It's not enough to solve them once; they require intensive practice!

# Using Greedy to Solve Interval Problems

The interval problems are memorable—there was a week dedicated to them, discussing all types of coverage and exclusion.

- 0055.Jump Game (opens new window)

- 0045.Jump Game II (opens new window)

- 0452.Minimum Number of Arrows to Burst Balloons (opens new window)

- 0435.Non-overlapping Intervals (opens new window)

- 0763.Partition Labels (opens new window)

- 0056.Merge Intervals (opens new window)

# Other Challenging Problems

0053.Maximum Subarray (opens new window) is typically a dynamic programming problem, but it's optimized in a greedy approach. It was a revelation for many that greedy could outperform dynamic programming.

0134.Gas Station (opens new window) might seem like a simulation problem but even as a simulation, it's not straightforward and may require proficient use of while. However, a greedy approach could reduce the time complexity significantly.

Lastly, the final challenge in the greedy series: 0968.Binary Tree Cameras (opens new window). The greedy solution is not easy to conceive, and it requires expertise in binary tree operations, a classic cross-section difficult problem.

# Weekly Summary of Greedy

Weekly summaries address doubts from the week's problems, discuss key challenges or errors, and provide a review and recap.

If you notice errors in the articles, whether in the weekly summary or the comments section, corrections would have been made to ensure there’s no misinformation due to my oversight.

So make sure to read the weekly summaries!

- Weekly Summary! (Greedy Algorithm Series 1) (opens new window)

- Weekly Summary! (Greedy Algorithm Series 2) (opens new window)

- Weekly Summary! (Greedy Algorithm Series 3) (opens new window)

- Weekly Summary! (Greedy Algorithm Series 4) (opens new window)

# Conclusion

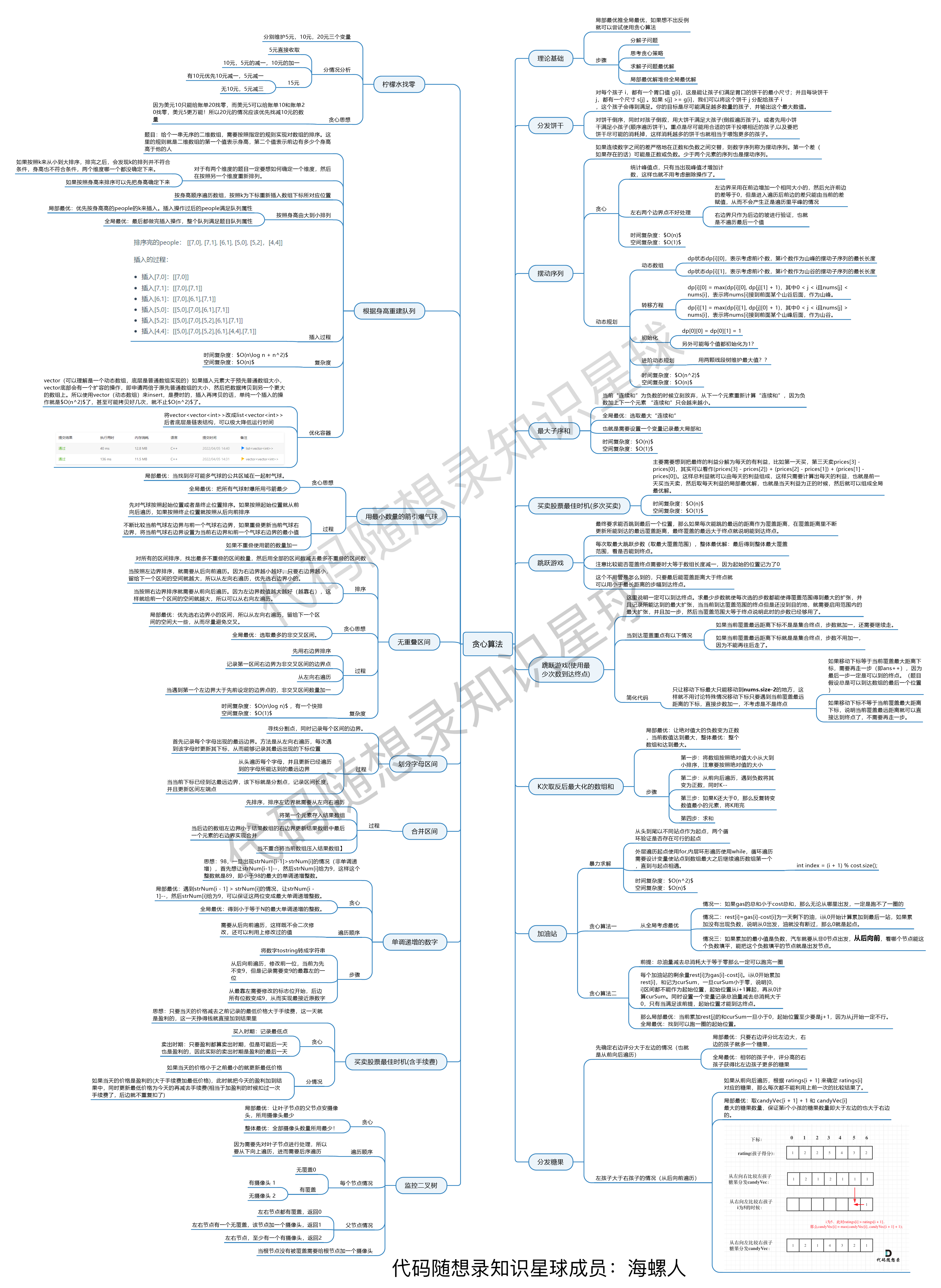

The greedy series culminates in a single diagram:

This diagram was diligently created by Hai Luoren from the Keetcoder Knowledge Planet (opens new window), and is an excellent summary shared with everyone.

Those who haven't encountered greedy algorithms might wonder about their significance. But following "Keetcoder" consistently will reveal that the greedy methodology is a vital algorithmic mindset, often surprisingly ingenious!

Reflecting on our initial introduction to the greedy subject, we see noticeable progression through persistence!

This aligns with the essence of what "Keetcoder" envisions: with consistent effort, a strong foundation and remarkable advancement naturally follow.

Across these eighteen classic greedy problems, I've clearly explained the local and global optima in each solution, which I believe distinguishes a proper greedy problem. If a local optimum isn’t discernable, it tends to be a simulation problem.

As one series comes to a close, it marks the commencement of a new one. As 2020 draws to an end and the first working day of next year approaches, we will officially kick off with dynamic programming. Time to board the train and not fall behind, as we embark on yet another new journey!